I was sorting through my photos on Sunday and found this one: it's a free-living caddisfly larva, the photo dated 12/11/11. I found this in the little stream in Sugar Hollow to which I returned yesterday. I had made no attempt at species identification. But the larva was preserved in my collection so I decided to give the ID a try. I've concluded that it's R. banksi -- or better, part of the R. banski complex -- which in turn is part of the R. invaria group. The R. banski complex includes the following species: R. alabama, R. banksi, R. carolae, R. kondratieffi, R. shenandoahensis, and R. parantra. (See A.L. Prather and J.C. Morse, "Eastern Nearctic Rhyacophila Species, with Revision of the Rhyacophila invaria Group," Transactions of the American Entromological Society 127 (1): xx-xx, 2001, pp. 104-106.)

How do we arrive at the R. banksi ID? To identify species of Rhyacophila you must examine the anal prolegs. Three questions: 1) do they have "apicolateral spurs"? 2) are there "basoventral hooks"? and 3) are there "ventral teeth" on the anal claws? We find all three, for example, on Rhyacophila fuscula.

apicolateral spurs

basoventral hook (a dark, hooked sclerite at the base of the anal proleg)

and ventral teeth (in this case two)

Steven Beaty says very little about the R. banksi complex: "larva ?? mm; head broadens posteriorly and without a conspicuous pattern." ("The Trichoptera of North Carolina," p. 60) It is very clear in my photos that the head does broaden from front to back.

But there is a very detailed description of the species R. banksi, along with illustrations, in an article by J.S. Weaver and T.R. Illand Sykora: "The Rhyacophila of Pennsylvania with larval descriptions of R. banksi and R. carpenteri", Annals of the Carnegie Museum, 48 (1979), pp. 403-423. Let me quote from that work (as cited in an unpublished manuscript by Joe Giersch and Robert Wisseman):

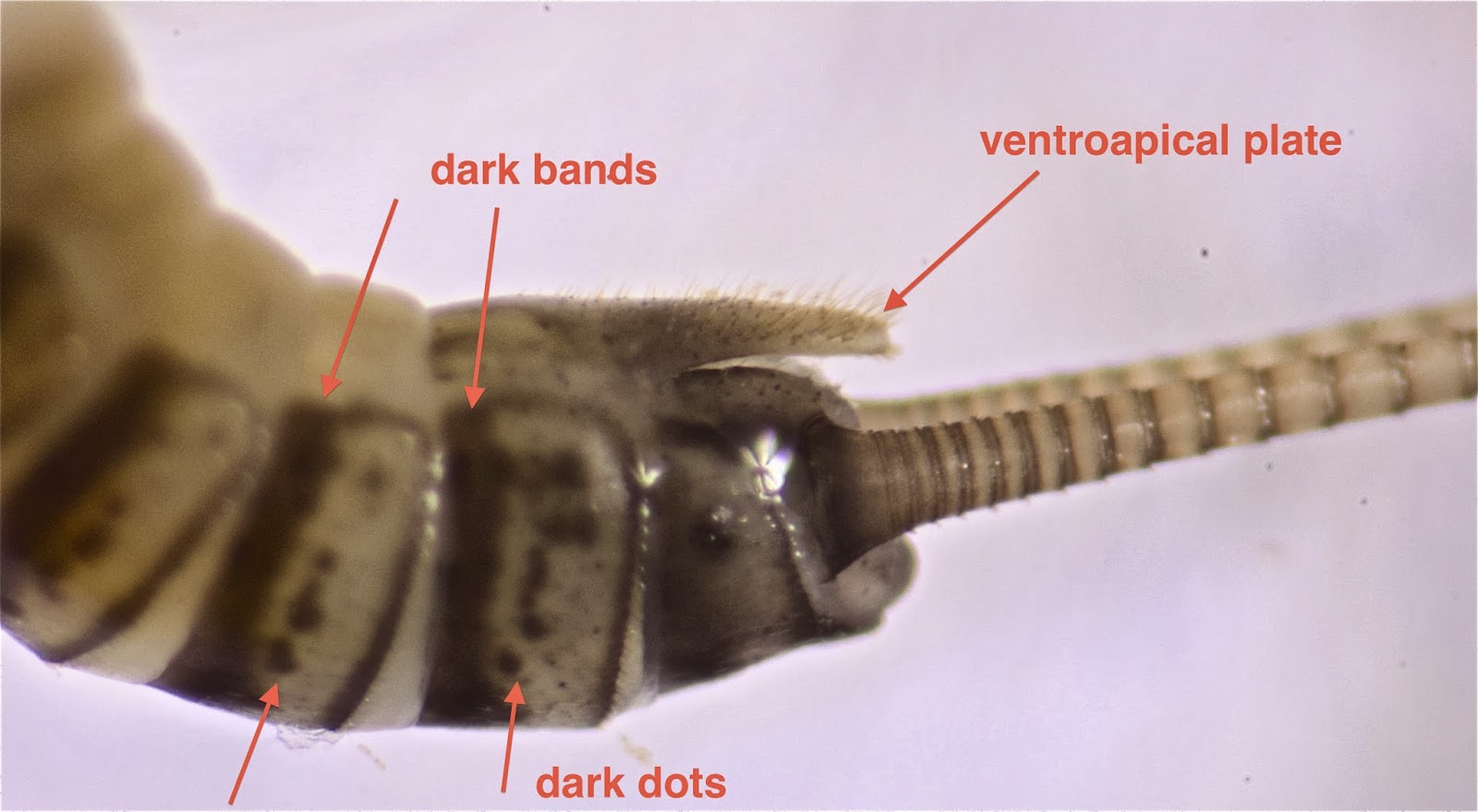

"R. banksi -- Overall length 16 mm, Head: Coloration variable; in some, golden brown, in others dark brown with an irregular row of pale muscle scars extended on each side of the front and the coronal suture, muscle scars faintly distinguishable on the frontocephalis, lateral and posterior portions lighter; right mandible with three apical teeth, mesal tooth longest; left mandible with two apical teeth, ventral tooth longer; maxillary palpi with second segment twice as long as the first. Abdomen: Proleg with basoventral and apicolateral processes, neither free of membrane; claw with one large ventral tooth and sometimes a smaller tooth. Flint (Roback, 1975) was of the opinion that "it is impossible to separate the larvae of R. invaria, R. shenandoahensis, and R. vibox." Likewise, we are unable to distinguish the larvae of R. banksi from these three species."

(Prather and Morse could not distinguish the larvae of R. banksi, R. shenandoahensis, and R. parantra.)

The head of our larva, viewed through a microscope, is largely dark brown with muscle scars along both of the sutures and muscle scars in the frontoclypeus: those at the rear are very light. It is an exact match, by the way, to the illustration provided by Weaver and Sykora and a close match to the illustration of R. parantra in Prather and Morse (p. 163).

While our article says that apicolateral spurs and basoventral hooks are present, it adds that neither is free of the membrane -- which is to say they're not "present" in the way that they are on something like R. fuscula. (You can see the sclerite on our larva -- but it's not really "hooked".)

There is one large tooth (denticle) visible on each ventral claw, possibly a second which is quite small.

Clearly, I need to check the "mandibles" with care -- but I'd rather have a second larva before I dismember the head of the only one in my collection. One other thing -- the pronotum of R. banksi, as illustrated by Weaver and Sykora, is an exact match to the pronotum we see on our larva.

_________________

I think there's good reason to feel that the larva I found in December 2011 was indeed a member of the R. banksi complex, though clearly this ID is a tentative one. But if that is true, it would mean that I've now found five Rhyacophilids in this one little stream.

R. fuscula

R. nigrita

R. glaberimma

R. carolina

and now R. banksi (one of the "complex")

That's pretty special. But this is a real special stream.

________________

(Hmm... is this the same insect? Same stream on 3/14/11. Rhyacophilids are "predaceous," and that Chloroperlid's in trouble!)